I recently had the opportunity to visit the Chinese cities of Xiamen and Taipei back to back. Located across the Taiwan Strait from each other, the cities are very similar in many ways: economically prosperous, around 5 million population, balmy subtropical climates, coastal locations with plenty of seafood, speak Minnan and Mandarin, and are both popular tourist destinations.

Yet there is one very obvious difference: after 1949, Xiamen on the mainland became part of the People’s Republic of China, while Taipei, on the island of Taiwan, became the last stronghold of the Republic of China. In the 75 years since the two have drifted hugely apart, and the experience of visiting them as a non-Chinese tourist couldn’t be more different.

Calibration note: As a fluent-ish Japanese speaker (N1) who has casually studied Chinese on and off for a long time, I’m in the somewhat odd position of being able to read basic Chinese while being quite bad at speaking or listening. If you don’t know any Chinese at all, you’re going to have an even harder time.

Xiamen 厦门

This was my first visit to mainland China since COVID (2018, to be precise) and my first time in Xiamen as well. With a mere 24 hours on the ground, I’m not going to claim to have anything more than a casual tourist’s understanding of what was once the treaty port of Amoy, but even this casual scratch of the surface left us with strong impressions.

First the good news: there have been two major improvements for foreign visitors since 2018. China now grants visas on arrival for citizens of many countries including Australia, avoiding the previous visa application rigmarole or the need to queue up for a special transit visa, and you can now add foreign credit cards to Alipay (支付宝 Zhifubao), which is a real lifesaver since not once did I see anybody use cash.

But most things had not changed. The PRC remains a surveillance state, and if anything the iron grip of the Chinese Community Party has been ratcheted tighter since 2018. Driving along any larger street, there are constant flashes as automatic license-plate recognition systems record every movement of every car. Larger and smaller streets alike are festooned with cartoonish Christmas trees of CCTV cameras. And there are tons of police patrolling the streets, both actual cops (警察), urban enforcement (城管), Public Security (公安), etc. Strolling down surprisingly quiet Zhongshan Rd, Xiamen’s most-polished shopping street, on a Monday night, the only real sign of life was a large police festival where elementary school kids got to hold submachine guns while posing next to grinning fully decked out SWAT teams.

I knew from experience to not to expect much English, but I was still surprised to find that even people in jobs that interact regularly with foreigners either really struggled (eg. staff at our Western-branded hotel) or spoke zero English whatsoever (check-in agents at XMN airport, Gulangyu ferry ticket sellers). While roads and directions were admirably well signposted in English, basically nothing else including shop or restaurant signs was. My Mandarin definitely got a workout.

This is an unfortunate combo with another classic PRC/post-Communist trait, the lack of customer service culture. This is not so bad when you’re at (say) a restaurant that has to compete for customers, but a lot of petty bureaucrats doing things like queue control quite clearly hate their jobs and don’t even bother to try to hide this, straight up yelling at people in the wrong line etc. And if you’re a square peg like a non-Chinese-speaking foreigner trying to squeeze into a round hole intended for ID-carrying Chinese citizens only, things get complex pretty fast.

This was most dramatically illustrated by the pain of trying to get to Xiamen’s top sight Gulangyu, a car-free island that was once home to China’s second International Settlement after Shanghai and, thanks to nearly a century of Westerners living there, is famous for its musical heritage and architecture. By some accounts the world’s most visited UNESCO World Heritage site, to control the crowds you can only enter via special tourist ferries. Helpfully, you can buy advance tickets online from Xiamen Ferry; unhelpfully, the only way to buy them is via their official Alipay/Wepay minisite (Chinese only, of course), which intentionally blocks all access if you are not within the loving embrace of the Great Firewall. Even roaming on a foreign mobile in China doesn’t cut the mustard, only a local network will do. Once you clamber over this obstacle, you run into two more that the average foreigner will find impassable: you need to have Chinese ID to buy tickets, and you need to have a Chinese mobile phone number to get the link to the magic QR code.

This left us with only one option: party like it’s 1999 and buy tickets in person. Since approximately nobody does this in terminally-online China, the only manned ticket counter at the massive International Cruise Center building that serves all Gulangyu tourists and approximately zero international cruises is hidden on the 3rd floor, tucked away behind cafes and teddy bear shops. Departure boards were entirely in Chinese, but I was able to pick out 三丘田 as my destination and ask for it. The grumpy lady responded with a lengthy burst of rapid-fire Chinese way above my skill level, then repeated it word for word after my tingbudong. Eventually she sighed and scribbled out 9:50 ¥80, 10:10 ¥35; she had been asking me if I wanted the fancy boat or the regular ferry. I opted for the cheaper sanshiwu kuai option and handed over our passports, and after a few more rounds of charades I was in possession of three tickets for departure in just under an hour. Fortunately it was a low-season weekday; I gather multi-hour waits or even selling out entirely is not uncommon.

Then it was security time. Getting on this local ferry required airport-style security: queue up at the correct departure line, validate tickets against passports, put belongings through metal detector, get a half-assed patdown, then wait in a cattle pen. Boarding started 10 min before departure, but everybody queued up 30 min early in a randomly pulsating gaggle, ignoring attempts to form them into orderly queues. Yet another ticket check, down a staircase with speakers yelling XIAOXINTIJI (mind the steps) every 10 seconds, onto a standing room only ferry where an extremely high-pitched announcer proceeded to regale us with endless hype about how everything we were seeing was 中国最X (biggest/longest/oldest/… in China) until, to general amusement, the batteries in her microphone abruptly died and we got to enjoy the sight of her desperately yet unsuccessfully whacking it with her palm to make it work again. Ah, glorious silence!

After all this Gulangyu was blessedly peaceful, since even a few steps outside the ferry terminal the crowds died down. We had the beach to ourselves on a sunny January day and neither was there anybody else in Mr Lin’s famous satay noodle joint at 11:30 AM. Getting the ferry back was painless too with no security or queuing rigmarole, we were on our way back in 10 min and this time on the spiffy air-con ferry, with no extra charge.

But a final wrinkle awaited. Since we hadn’t bought any souvenirs from Gulangyu, I wanted to pick up some at the ferry terminal mall, so we didn’t follow the signs for Arrivals and went back to Departures instead. Once we did, there was zero signage about how to go against the flow and it was very unclear where to go hail a Didi. Eventually I spotted a small Chinese-only 网约车 (net-booking-car) sign and followed it to find more signage to a Departure Plaza, only to find our path blocked by construction and no clue where to go next. We detoured via the road and finally were able to hail our car, which like all our Didis in Xiamen was ridiculously cheap by Western standards (¥15, ~US$2) and, since Didi does have an English UI, was very straightforward to navigate. Credit where it’s due.

Last and least, a grab bag of small surprises. Xiamen Airlines had boarding announcements in Fujianese (Minnan). Off season, the rather swish Le Meridien hotel in Xianyue Park was quite affordable and, surrounded by green hills, felt a world away despite being right in the city. There was a series of very flashy albeit entirely deserted “Ura!” (Ура!)-branded Chinese-Russian International Shops (中俄国际商场) in central Xiamen. And while both the satay noodles I sampled were a bit of a disappointment, with watery broth that only barely tasted like peanuts, the taro paste fragrant crispy duck (芋泥香酥鸭) was better than any orh nee I’ve had in Singapore.

Taipei 台北

A one hour flight yet a world away, we landed in Taipei’s Songshan city center airport. Immigration was a cinch and soon enough we were in a much more expensive Uber (those $2 rides were now $15 rides), marveling at the bright lights of Xinyi. The air quality wasn’t much better on this side of the strait, but Taiwan was still a breath of fresh air.

Maybe it’s a holdover from Japanese colonization, maybe it’s simply from not being suffering through the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, but Taiwan just felt so much more gracious after the PRC. Out for an early morning walk to get breakfast, I walked past a security guard at a random office building, who gave a friendly salute and smiled. Grabbing some danbing (蛋餅) egg crepes and soymilk at a busy little hole in the wall, the cashier dug up an English menu and settled the bill in fluent English. On my way to exchange money at an office building, the maintenance guy waiting for an elevator with a fully-loaded cart waved me in first. All tiny little things, but they made me feel welcome, instead of feeling like a nuisance like I often do in China.

Partly this is because Taiwan is clearly a high-trust society. There is no security theatre on the Taipei Metro, and people queuing for the Maokong Gondola or a table at Din Tai Fung do so without needing a recorded announcement every 10 seconds or an angry lady with a megaphone yelling at them. You can stroll right into Chiang Kai-Shek’s mausoleum, commemorating a man the Taiwanese themselves have distinctly mixed opinions about, or into the National Palace Museum, hosting the world’s largest treasure trove of Chinese art, and nobody will stop you to inspect your backpack. There are no sketchy touts at Songshan Airport, and I paid street vendors in cash and always got the correct change back down to the last cent.

Taipei also feels alive in a way that Xiamen doesn’t. Most buildings are older and more grungy, with that spotty layer of black mold that coats every concrete surface in the subtropics (outside Singapore, where all houses have to be repainted every few years), but they’re also decorated with murals, straight up graffiti and stickers, all totally absent from central Xiamen. The few temples on Gulangyu are Historical Sites marked with brass plaques and no visitors; the countless temples, big and small, of Taipei are well-patronized by all in the neighborhood, and we even ran into a mildly obnoxious if harmless lady in the MRT who invited us to her church and told us that Jesus is a great guy.

Unlike monolithic China, Taiwan also retains some non-Chinese history, with the Japanese era in particular remembered with surprising fondness. The spa town (suburb, really) of Beitou to the north of Taipei has numerous Japanese-style baths like the somewhat scarily named Radium Kagaya, a branch of the famous original in Wakura Onsen, and indeed every major Japanese department store, convenience store, hotel group and restaurant chain seems to have a toehold in Taipei. Even the long-suppressed indigenous population seems to be getting some recognition, with a prominent Ketagalan cultural center in Beitou, and Zhongshan Hall was decorated with Polynesian-looking curlicues that wouldn’t look out of place in a Maori tattoo.

I’m having a hard time pinpointing why, but while Xiamen felt like mainland China with a few more palm trees, Taiwan feels like Southeast Asia, even in midwinter when the climate certainly doesn’t. (The effect was even more pronounced on my last trip in steamy mid-August.) The Taipei Metro was straight out of Singapore, the night markets of Linjiang St could have been in Kuala Lumpur, the tea plantations of Maokong could have been in the Cameron Highlands, the flashy shopping streets of Xinyi could have been in Bonifacio Global City. And there are quite a few actual Southeast Asians in the mix, with nearly a million people from the Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam forming a visible minority in Taipei and almost 5% of Taiwan’s population. Incredibly, this is a larger absolute number than the total of foreigners living in mainland China, who number around 710,000 out of 1.4 billion (0.05%).

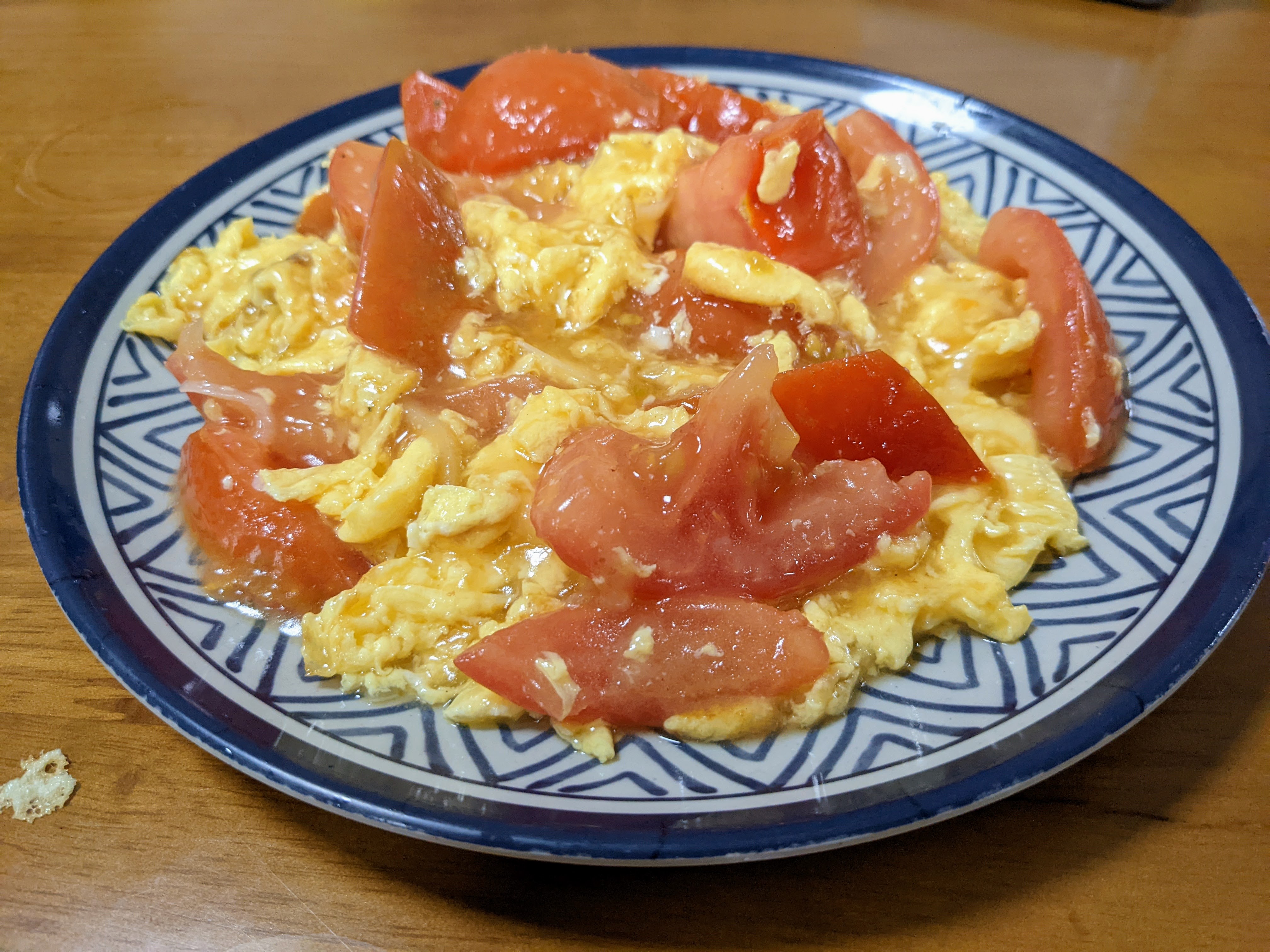

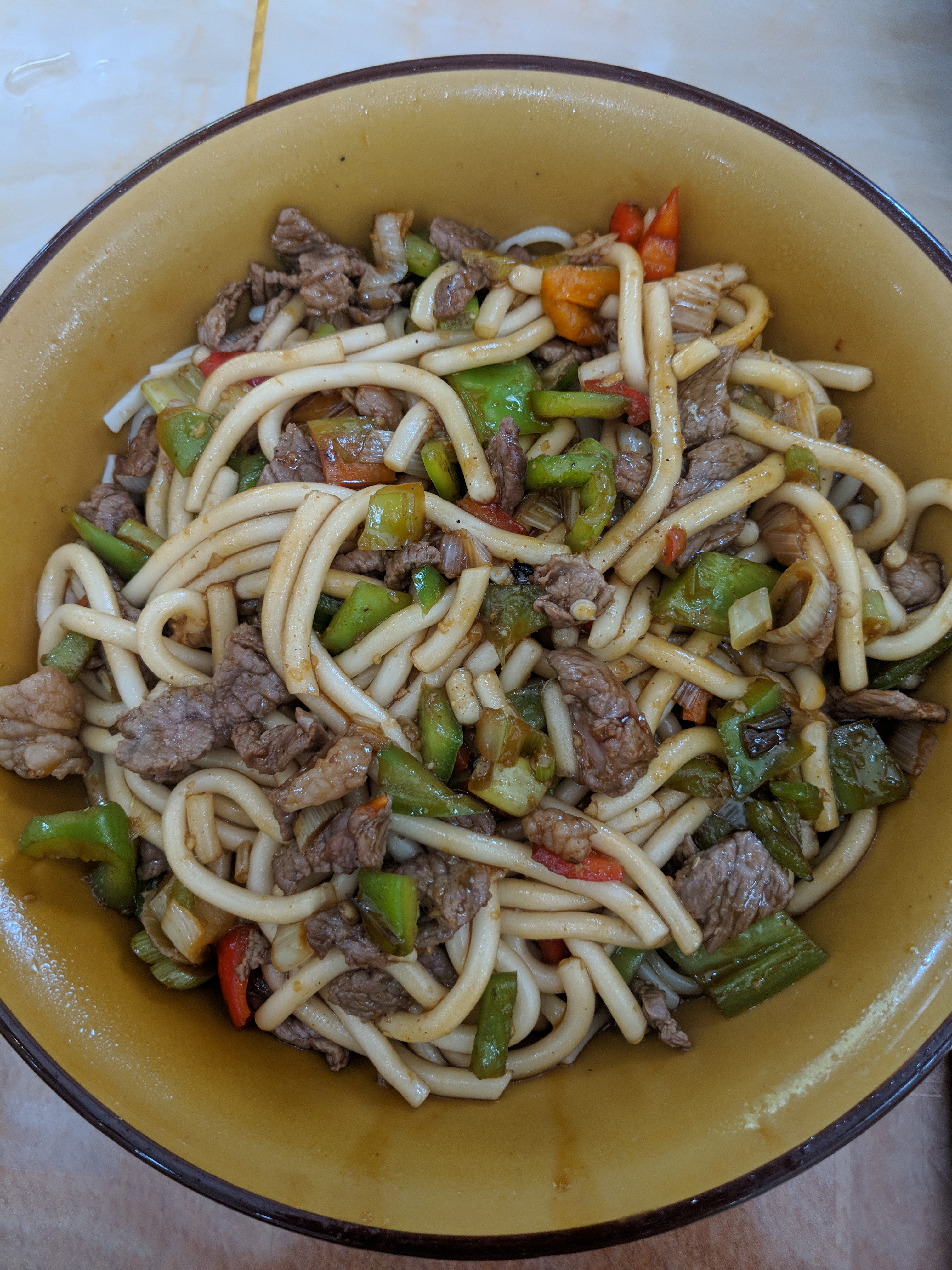

Last but not least, Taiwanese food! Dumpling masters Din Tai Fung, street food from the night markets, luroufan minced pork rice from super friendly little hole in the wall in Beitou, tea oil noodles in Maokong, beef noodles in Ximending, we didn’t have a single bad meal during the week. Even the stinky tofu was good. And the price was right too: 50 TWD (US$2) gets you a basic meal, 500 TWD (US$20) is enough for a feast.

To wrap it up, if you’re a China first-timer or you’re choosing between Xiamen or Taipei, Taiwan wins, hands down. There are still plenty of places on my to-do list for the mainland (Chongqing, Yunnan, Gansu…) and I’ll be back sooner or later, but I just might end up exploring Taiwan a little more first.