Guangdong (“Eastern Expanse”) sits on the shores of the South China Sea, enveloping Hong Kong and Macau. Still better known to many as Canton, a label confusingly also applied to its capital Guangzhou, Guangdong is China’s most populous province and its most prolific source of emigrants. If your city has a Chinatown, or even an “old-school” Chinese restaurant targeted at non-Chinese, odds are they were founded by Cantonese, and Chinese cuisine as found in the West is largely built on Cantonese roots.

Interestingly, while Cantonese culture and language predominate among the Chinese in many overseas Chinese communities including much of neighbouring Malaysia, in Singapore they’re third place at best. So for this episode, I’m also going to try to cover the cuisine of two subgroups also originating from Guangdong: the Teochew and the Hakka.

Cantonese (Guangdong) 广东

Cantonese cuisine (粤菜 yuècài) is well regarded in China, and according to a well-known saying, you should be born in wealthy Hangzhou, marry a beautiful denizen of Suzhou, eat in tasty Guangzhou, and die in Liuzhou because, uhh, apparently their wood makes the best coffins. Cantonese food is typically characterized as being light on spices and oil, instead emphasizing quality ingredients, and there are so many Cantonese restaurants in Singapore that the hardest part was really choosing what to eat and where to go.

I started by exploring siu mei (燒味), literally “roasted tastes”, the umbrella term for Cantonese roasted meats. Every self-respecting hawker centre in Singapore has a roast meat (烧腊 siu laap) stall or two dishing out the standard trio of sweet red char siu (叉燒) barbecued pork, salty crispy siu yuk (燒肉) pork belly, and siu aap (燒鴨) roasted duck, but one Cantonese meat that’s not so easy to find in Singapore is siu ngo (燒鵝) roast goose. Likely the world’s most famous purveyor of this is Kam’s Roast Goose (甘牌燒鵝) in Hong Kong, where I’d once made a pilgrimage only to be denied (sold out!), so I tried my luck again at their Singapore branch at Jewel. Alas, there’s no roast goose on the menu here, because you can’t legally import it from China! For lack of better options I tried the roast duck noodles, which were lukewarm, greasy and distinctly forgettable despite the steep $10.80 price tag, 3x what you’d pay at a hawker. The one goose dish they did have on the menu, Cured Goose Liver Sausages (鹅肝香肠), was really gamey and kind of overpowering — and I say that as the guy who always orders the liver at roast duck joints. Quite disappointing.

The most famous Cantonese tradition, though, is dim sum (点心), the vast array of “small hearts” eaten at family weekend brunches and washed down with copious quantities of tea — hence the name yum cha (饮茶), “drink tea”, for entire operation. Tim Ho Wan from the Hong Kong episode did not satisfy, so round 2 was a company event at a far more high-SES option, the Michelin-starred Summer Pavilion (夏苑) at the Ritz-Carlton. You can easily blow $500/head here on Japanese kippin abalone if you’d like, but since the generosity of my corporate masters is not entirely unlimited, we stuck mostly to the dim sum lunch menu, where most dishes clock in at $7.50/plate. There are only 12 options here, all of them with a little twist on the usual: for example, the classic char siu bao (叉烧包) buns have a hint of meicai preserved vegetable, the crystal dumplings (水晶饺) hide beancurd and Sichuan vegetable, the delectably light and fluffy deep-fried taro balls (芋角) have scallops and cream, etc. One unique option was the Pan-Fried Shredded Yam Pumpkin (金瓜煎芋丝), where the “yam” (actually taro) had a crispy exterior, a chewy, mochi-like inside and a layer of pumpkin paste in the middle. Venturing a la carte, we dialed up a Barbecued Combination Platter (the roast duck was quite good), a chive & beansprout stir-fry with bits of you tiao fried breadsticks (!), braised beancurd with bamboo and a bowl of “Hong Kong” (伊麵 yi mein) noodles, thin wheat fettucine-ish noodles that are cooked until they soak up the broth and served almost dry, the classic end to a Cantonese banquet. Total damage for 4 was $240, not exactly cheap given that I was complaining about $10 noodles earlier, but not entirely unreasonable for food of this caliber and definitely worth checking out if you’re tired of the usual har gaos and shu mais. (Random reco: Jade at the Fullerton also does excellent fancy dim sum, but they’re straight-up fusion with things like chilli crab buns and red wine dumplings.)

A common dim sum dish I’d never really gotten into is chee cheong fun (猪肠粉), literally “pig intestine noodle” but usually rendered into English more palatably as “rice noodle roll” or similar. Despite the name, no pigs are involved in the production process. They’re made by steaming a sheet of watery rice flour batter, carefully peeling them off the cloth, adding any toppings and rolling them up so they resemble intestines. As the rice has very little taste, they’re served with a slightly sweet soy dressing and, this being Singapore, some chilli on the side. Chef Wei HK Cheong Fun in Bishan is a newly-founded but hugely popular chain specializing in nothing but the stuff, and despite the $4-5 price tag there was a line before 8 AM on a Thursday morning. With plain, mushroom, char siu, and shrimp on the menu, I picked the shrimp and hot damn, this was really good. Silky smooth texture, considerably larger than your average portion, and being still warm made it so much better. Two thumbs up. I’ve become a regular now, and their dough stick cheong fun is also great, with crispy, extra-fried bits of you tiao fritters providing a great contrast to the rolls.

I’d like to jabber on for another few pages, and I’m feeling really guilty about missing out on the vast array of Cantonese soups, fresh seafood, rice porridge, claypot rice, tong sui (糖水) desserts and more… but I’ve got two more entire cultures to plow through in this entry, so the duck stops here. Quack.

Teochew (Chaozhou) 潮州

The Teochews of eastern Guangdong make up the Singapore’s second largest dialect group, second only to the Hokkiens, and despite the province boundary are in many ways closer to their Fujianese cousins than to the Cantonese. Even the Teochew dialect is a branch of Southern Min, not Yue (Cantonese), and you should totally go listen to some because it’s about as far from Mandarin as you can get.

Teochew cuisine (潮州菜 Cháozhōu cài), unsurprisingly, is similar to southern Fujianese cuisine, with plenty of seafood on the menu, but a lighter touch on the seasonings thanks to the Cantonese influence and more poaching, steaming and braising than oily stir-fries.

We started our journey by sampling Teochew rice porridge (糜 mí, or mue in Teochew) at Ah Seah Teochew Porridge in Serangoon, perennially packed even in the COVID era. Unlike Cantonese congee (粥 zhōu, juk), slowly cooked and stirred until the rice dissolves completely and a meal in itself, Teochew mue is a light, milky rice broth with distinct grains, largely flavourless by itself but designed to wash down the accompanying array of delectables. At Ah Seah, you pick what you want from the economy rice -style glass case, and it’s brought to your table on a series of small plates. Lo bak braised meats, kiam chye pickles, omelette with chai poh (preserved radish), salted duck egg, stewed peanuts, steamed pomfret, springy fishballs, juicy meatballs, lala clams with chilli, ngoh hiang (five spice) pork rolls… we devoured most of it before I remembered to bring out the camera. And the cost for stuffing the four of us to the bursting point? $40.20. No frills, no air-con and no reservations, so get here before 6 PM if you want to find a table!

When I’m at a hawker and not quite sure what to eat, I default to a quintessentially Singaporean Teochew dish called bak chor mee (肉脞面), literally “meat mince noodles”, but the bland name hardly does the dish justice. I’ve eaten this dozens of time all over the island and am rarely disappointed, but the version served at Chai Chee Noodle Village (菜市潮州鱼丸面 Càishì cháozhōu yúwánmiàn, “Chai Chee Teochew Fishball Noodles”) in Ang Mo Kio is particularly magnificent. At a regular “BCM” place, for around $3 you’ll get fettucine-like flat egg noodles (mee pok) with minced pork, thinly sliced pork liver, fish balls, slices of fish cake, stewed mushrooms and sinfully delicious crispy bits of fried lard, tossed in a chilli and vinegar sauce and served with the cooking broth on the side. Here, you pay $2 extra but get no less than 18 ingredients in your bowl, all of them primo quality.

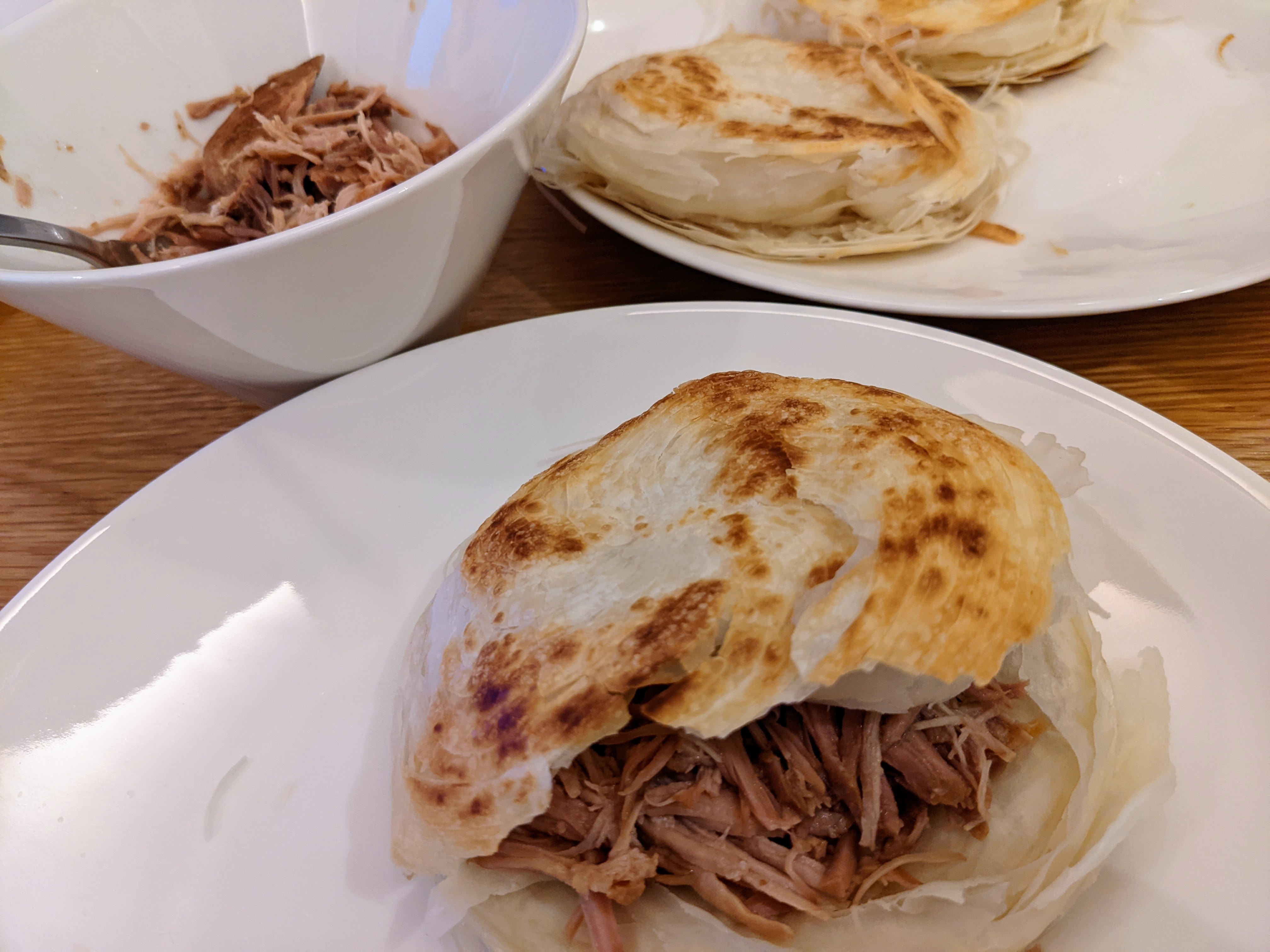

More a snack than a meal is the popiah (薄饼 bóbǐng), often described as the Teochew take on spring rolls, and I had one to celebrate my 2nd shot of Pfizer at the thoroughly un-famous yet popular Ding Wang (鼎旺) stall in the equally nondescript 151 Coffeeshop at Serangoon North Ave 2, near the vaccination centre at Serangoon CC. A popiah is a paper-thin wheat crepe — hence the name, “thin cake” — coated with sweet bean sauce and chilli paste, stuffed with soft steamed jicama (a turnip-like root), and wrapped up into a burrito of sorts. Each stall has their own mix of extra ingredients, here consisting of ground peanuts, chopped boiled egg, julienned cucumber (I think?), but only a bit of each so the flavour was dominated by the jicama and the pretty zippy chilli underneath. At $1.80 a pop(iah), it was OK but hardly worth a detour.

The Teochew are also known for their kueh (粿), a concept that doesn’t fit easily into any one English word. In Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, it has been adopted to refer to a vast range of Malay/Indonesian snacks and cakes, mostly based on rice flour, tapioca and coconut milk, often colourful and usually sickly sweet but delicious. Original Teochew kueh, however are mostly steamed, savoury concoctions particularly popular for breakfast, and I queued up at Fatt Soon Kueh (发笋粿) in Kovan to test out if the implied threat in the name should be taken seriously. (Spoiler: Yes. Although the fatt here is Cantonese for “prosperity”, not increased belt size.)

Despite the dine-in ban at the time, at 7:30 AM there was already a long queue outside, waiting for the two ladies manning the stall to roll out, stuff and steam their kueh from scratch while you wait. The star of the show was the eponymous soon kueh (笋粿), “bamboo shoot kueh“, a steamed rice and tapioca flour dumpling stuffed with a crunchy, spiced mix of jicama, bamboo shoot, dried shimp. Piping hot, these were absolutely delicious and enough for me to completely revise my view of what I’d always thought were gluggy, mediocre facsimiles of “real” dumplings. They also sell ku chai kueh (韭菜粿) stuffed with chives, which were OK but pretty oniony even for a chive fan like me, and png kueh (飯粿, “rice cake”), dyed a pretty pink and stuffed with heavy glutinous rice, making a bit of an odd combo with the soft exterior. Verdict: the soon kueh are absolutely worth the wait and a steal at 3 for $3, the other two are skippable.

Hakka (Kejia) 客家

Of all the Chinese dialect groups, the Hakka have the most interesting origin: it’s effectively unknown. The best we can tell, sometime around 200 BC (!) the ancestral Hakka started moving south from northern China near Gansu, ending up thinly spread across much of the country but with some 60% of Hakka speakers eventually landing in Guangdong. The locals weren’t always happy about these “guest families” (the literal meaning of the name) showing up, with around 500,000 massacred in the 1850s, and unsurprisingly many of the survivors chose to migrate overseas. One of them was Lee Bok Boon in 1862, the great-grandfather of Singapore’s most famous Hakka, prime minister Lee Kuan Yew.

Given this geographical dispersion, Hakka cuisine (客家菜 Kèjiā cài) is a little hard to pin down. but usually it’s described as simple and rustic: lots of tofu, pork and pickles, not much in the way of seafood. The quintessential Hakka dish is lei cha fan (擂茶饭 léichá fàn), literally “pounded rice tea”, but often rendered in English as “thunder rice tea” since 擂 léi “pounded”, written with the “hand” and “thunder” radicals, sounds exactly the same as 雷 léi “thunder”. The key ingredient is (surprise!) finely ground tea, not entirely unlikely Japanese matcha, but made with various other herbs mixed in and served as a hot soup. Born out of poverty and long rather obscure, it has recently undergone a bit of renaissance as a trendy health food and there’s even a dedicated chain called Thunder Tea Rice now. (The pictures above were taken a few years ago at their now closed Lau Pa Sat outlet, in the heart of the financial district.) In the modern interpretation as shown here, the bulk of the dish is a bowl of rice topped with peanuts, shredded cooked cabbage and beans, dried radish and crispy dried tiny anchovies (ikan bilis in Malay). The lei cha, deep green, herbal, funky, often a bit bitter, is served in a separate bowl on the side, to be spooned into the rice or drunk straight as you prefer. Always a nice change of pace, and vegan too if you skip the anchovies.

But I was keen to explore more, so it was time to pay a visit to what, astonishingly, appears to be the only remaining Hakka restaurant in Singapore, Plum Village (梅村酒家 Méicūn jiǔjiā) off Upper Thomson Rd. Opened in 1967 and now run by the 3rd generation of the Lai family, precisely nothing appears to have changed in the 50+ years since, with daggy-but-homely red lanterns, Hakka poetry and landscape paintings on the fake brick veneer walls. It’s also the only restaurant I’ve been to in Singapore that has both only an Asian-style squat toilet and a menu exclusively in Chinese, but fear not, ordering is easy: just get the set for 4 people (4人配套), and you’ll get the full Hakka hit parade. Abacus seeds (算盘子 suànpánzǐ). named after their resemblance to the beads of an abacus, are the Hakka equivalent of gnocchi, soft doughy balls of tapioca and yam fried with dried shrimp, bits of mushrooms and a sprinkling of chives. Yum! Pork belly with preserved mustard greens (梅菜扣肉 méicài kòuròu) was great, the fatty meat smoothly melting into a generous salty, tangy pile of what Singaporeans usually call mui choy. The salt-baked chicken (盐焗鸡 yánjú jī) was OK but not terribly exciting; despite the name, it’s steamed, not baked, and was basically a saltier version of the ubiquitous Singaporean/Hainanese chicken rice. The tau pok (豆卜) fried tofu puffs stuffed with minced pork were piping hot and delicious, and last but not least, we had a heaping plate of Hakka egg noodles with pork (肉碎面 ròu suìmiàn), which to me looked and tasted an awful lot like the Cantonese yi mian often served as the last course of a banquet. At $48 for the whole shebang, including endless tea refills, this was almost absurdly good value. Two thumbs up, and easily one of my top picks for the journey so far.

Yet I was still missing probably the most popular Hakka dish in Singapore, namely yong tau foo (酿豆腐 niàngdòufu), inevitably abbreviated as “YTF”. In Singapore, this is usually served at stalls that operate with a “salad bar” concept: pick what you’d like, specify how you’d like it prepared, and then pay per piece. The selection is often huge (see above), with veggies, sausages, fake crab, seafood etc, with my personal default order being “dry” (soup on the side) with yellow mee noodles, plenty of mysterious sweet brown bean sauce and a little dish of sambal chilli on the side to dip into. The keen reader will note that this setup is quite similar to how mala xiangguo shops operate, and the double whammy of mala and COVID has definitely trimmed the numbers of the once ubiquitous YTF stalls, since this is also not very delivery-friendly.

However, the original Hakka style is much simpler, and I ventured out to Koo Kee Yong Tow Foo Mee (高記釀豆腐面) at Bishan’s recently reopened Kim San Leng (金山嶺) coffee shop to try it. This is a chain with firm opinions about their recipe, which remains unchanged since 1954: your yong tau foo will consist of a bowl of soup with exactly five things, which are tau hu (豆腐, tofu with fish paste), tau pok (豆卜, tofu puff with fish paste), tau kwa (豆干, fried hard tofu with fish paste), tau kee (豆皮, bean curd skin with fish paste) and a single fish ball made with, you guessed it, fish paste. With grandmotherly kindness, they do permit you to choose your noodles, so I went with egg noodles on the side with a bit of minced chicken on top.

At this point, I’d like to wax poetic about upholding traditions etc, but truth be told, five pieces of bland fish paste and tofu just doesn’t taste all that exciting. One reason I like dry YTF is that deep-fried things stay crispy and everything retains its texture, but at Koo Kee you just get blobs in soup. Not super impressed, although I am curious about the “hot plate spicy” YTF on the menu. Next time…

And that brings me to the end of this monstrously long yet still sadly incomplete episode, with 10 hawkers and restaurants that still only scratched the surface of the province’s culinary offerings. But while comrades may fall by the roadside, hopefully buried in coffins of Liuzhou wood, the Long March continues.

<<< Hainan | Index | Heilongjiang >>>